The homefront during the world wars is a great place to look for strange technology and new social practices.

So, permit me a brief digression from green tech into the gender-bending agricultural and industrial story of Britain during the war told in the pages of the aforementioned 1918 National Geographics.

Judson Welliver tells us, “Everybody knows how British women have taken the places of men in industry, but nobody who has not seen can understand.”

Indeed the photos from the article are stunning. Hearty British “lumberjanes” sawing and cutting. A misty meadow of sheep attended by a “shepherdess”. The names themselves are strange, sort of like women’s college basketball team mascots: The Lady Vols, or what have you.

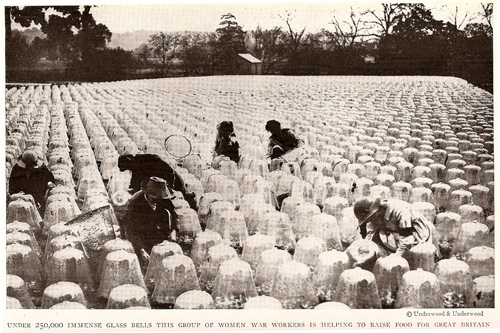

The most shocking photo, though, shows British women tending to 250,000 bell jars, each growing a single head of lettuce. These mini-greenhouses allowed the British to keep producing vegetables at a time when their fields would have normally lain dormant. (A larger version)

The caption reads, “UNDER 250,000 IMMENSE GLASS BELLS THIS GROUP OF WOMEN WAR WORKERS IS HELPING TO RAISE FOOD FOR GREAT BRITAIN.”

It continues:

The scene is Burhill Intensive Gardens, at Horsham, where, in compliance with the British Government’s instructions, every available inch of space is being utilized to supply British troops and civilian population with food. Under this sea of bells a quarter of a million heads of lettuce are cultivated.

Apparently this worked quite well, as Welliver tells us that in 1918, Britain “has produced foodstuffs enough to feed it for 40 of the 52 weeks,” a feat not accomplished for more than 50 years. All that food growing, though, left its mark on the land:

Sacred parks and beloved areas of grass lands have been sacrificed; but the food was produced, because there were no ships in which to import it. Not again will Britain permit itself to be dependent for its daily bread on the uncertainties of importation… The 1918 achievement would not have been so striking in normal conditions as to labor, animals, implements, fertilization, and the like; but in the circumstances of its accomplishment it is one of the war’s wonders.

Let’s leave aside for a minute all the gender stuff and just contemplate a group of people waking up in the morning for their first day at their new job, walking down the road to what used to be their favorite park, where they once strolled looking for cute boys, and seeing this “sea of bells.” This is not a field, it’s government projects for a species of plant; each and every lettuce head gets its own house to further its development and speed its way into the mouths attached to the system. And where’d they get all those Bell Jars?

That lettuce must have felt like the most special lettuce in the whole world, at least until it was plucked and boiled and eaten. Another reason to fear for your life if you find yourself living in a glass house.

It’s also sad that a quick search for “Burhill Intensive Gardens” — clearly one of the more insane experiments in agriculture you’re likely to find — comes up with a whopping 0 results. This is a PhD dissertation waiting to be written! The Bell jar and the Lettuce: An exploration at the intersection of solar energy, war, gender, and agriculture. (Perhaps this is my second book?)

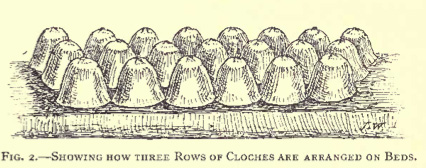

Here’s the first place to look for more information: the full-text version of this 1909 book about the gardeners of Paris. Apparently, Parisian urban gardeners employed the bell jars — called cloches — to protect their plants and raise salad greens early in the season. The book, first published in 1909, was designed as a practical guide to “intensive” farming the French way. Voila:

A promoter of this system, quoted in the book, had this to say to his British compatriots about the French and their stinkin’ cloches:

We have several important things to learn from the French, and not the least among these is the winter and spring culture of salads inasmuch as enormous quantities of these are sent from Paris to our markets during the spring months… The fact that we have to be supported by our neighbours with articles that could be so easily produced in this country is almost ridiculous. It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of this culture for a nation of gardeners like the British ; and if it were the only hint that we could take from the French cultivators with advantage, it would be well worth consideration.

It might have taken a world war, but the British got with the Francoculture, even if they appear to have abandoned it in later years.

Now, we can (sort of) return to our story, picking up the thread of the bell jar in agriculture with this article on “American intensive solar gardening,” written by a couple of hippy homesteaders, Leandre Poisson and Gretchen Vogel Poisson, in the 90s:

In 1976 Lea conceived of a gardening device that met all of his design requirements: it was inexpensive, easy to build, and used resources and energy wisely. We christened this device the Solar Pod. That fall we prepared a bed and planted it with lettuce, but we didn’t place the Pod on the bed until February. When we shoveled off the snow and uncovered the bed, which we had protected with a scrap of fiberglass, to our surprise the lettuce still looked green and edible underneath all that snow.

After we set the Pod in place, we were amazed by how the soil under it heated up and how the lettuce grew . . . and grew, and grew. It was quite possible the most photographed lettuce in history. Friends came to see the experiment, and they mentioned to us that the Pod reminded them of intensive gardens in France. The following winter we discovered several books on French intensive gardening, or what the French call the Marais system.

Eventually Lea designed what he thought of as a better cloche, too. He made it out of a material called “Sunlite,” produced by the Kalwall Corporation, that was a “solar-friendly, fiberglass-reinforced plastic sheet glazing material.” They wrapped it into a cone, leaving a hole at the top, and stuck it in the ground around the plants. “The best and final configuration, coincidentally or not, resembles the profile of the great pyramids,” they write. “We christened this lightweight modern cloche the Solar Cone.”

Next thing they knew, their plants were going wild. “The hole on the top permitted the necessary gas exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen, but inside each cone the environment resembled a miniature rain forest,” they surmised. All their success — and some appearances on the New England lecture circuit — got them thinking that maybe they’d actually come up with something new, a distinct American variety of an old European practice:

As we distilled and further refined our gardening system over the next decade, we began to realize that we were not longer translating the French system to America. We were in the process of developing our own unique system - a simple, state-of-the-art, flexible, and continuously productive method of growing food on very little land - which we named “American intensive gardening.”

While defining their agricultural system, they might have also hit upon the best short description of the mythical American: “simple, state-of-the-art, flexible, and continuously productive.”

Original here

No comments:

Post a Comment