Forty years later, we’re about to see what the moonwalkers left behind.

The shadow of their lander dominates a mosaic of the numbered photos Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took out their window before leaving the moon. (NASA/Panorama assembled by R. Farwell for the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal)

The shadow of their lander dominates a mosaic of the numbered photos Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took out their window before leaving the moon. (NASA/Panorama assembled by R. Farwell for the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal)

The flag is probably gone. Buzz Aldrin saw it knocked over by the rocket blast as he and Neil Armstrong left the moon 39 summers ago. Lying there in the lunar dust, unprotected from the sun’s harsh ultraviolet rays, the flag’s red and blue would have bleached white in no time. Over the years, the nylon would have turned brittle and disintegrated.

Dennis Lacarrubba, whose New Jersey-based company, Annin, made the flag and sold it to NASA for $5.50 in 1969, considers what might happen to an ordinary nylon flag left outside for 39 years on Earth, let alone on the moon. He thinks for a few seconds. “I can’t believe there would be anything left,” he concludes. “I gotta be honest with you. It’s gonna be ashes.”

There are other signs of aging at Tranquillity Base. The shiny gold foil on the base of the lunar lander is shiny no more—it would have darkened and flaked away long ago. The once-white life support backpacks, tossed out unceremoniously after Armstrong and Aldrin made their brief spacewalks, have likely turned yellow. The TV camera, the seismometer, the discarded hammer—anything made of glass or metal—are probably okay. And the famous bootprints? They may still be as crisp as the day they were made. Or, they may have the thinnest coating of dust from small grains moving around continually on the lunar surface (see “Stronger than Dirt,” Aug./Sept. 2006).

The truth is, no one knows exactly what the Apollo landing sites will look like after four decades. Nobody thought it would take us this long to go back.

And now we are.

New cameras in orbit around the moon have begun returning photos of sights unseen in a generation. Japan’s Kaguya spacecraft, which arrived in lunar orbit in October, took a picture of the Apollo 15 landing site in February that clearly showed a tiny patch of white on the dark gray landscape—dust disturbed by Dave Scott and Jim Irwin’s rocket engine as they touched down in Mare Imbrium in July 1971. They and other Apollo moonwalkers routinely photographed the white patches when they looked back at their landing sites from lunar orbit before returning home. Kaguya’s best camera has a resolution, or ability to separate two objects, of 10 meters (33 feet)—just enough to make out the white patch of disturbed soil. The camera can’t quite resolve the squat, 30-foot-wide base of the Apollo 15 lander sitting in the middle of that patch. But the Kaguya photo shows a dark feature that may be the lander’s shadow.

Until Kaguya, there hadn’t been a camera good enough to spot Apollo artifacts on the moon since the last astronauts left, in 1972. Neither the U.S. Clementine nor the European SMART-1 moon probes, launched in 1994 and 2003, respectively, had enough resolution. (In case you’re wondering, even the best ground-based telescopes can’t make out Apollo hardware on the moon. They have the resolution—some produce sharper images than the Hubble Space Telescope—but the objects left by the astronauts aren’t bright enough to be seen.)

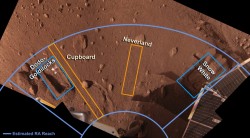

So it’s a job for lunar orbiters. Next up is Chandrayaan, India’s first planetary science spacecraft, which is due to arrive at the moon this fall with a camera twice as sharp as Kaguya’s. That should be good enough to see more than smudges in the dirt, according to Mark Robinson, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University whose own high-resolution camera will fly on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) in November. “I will be surprised if Chandrayaan can’t detect the [lunar landers],” says Robinson. The bases of the landers, six of which are still on the moon, will be only about two picture elements, or pixels, across in the five-meter-resolution images—not enough for clear identification. But in photos taken at low sun angles, says Robinson, the landers’ shadows should appear as dark streaks up to 10 pixels long. This technique has paid off in the past. Long before the first Apollo landing, scientists studying photos taken by the Lunar Orbiter 3 spacecraft noticed a shadow cast by the Surveyor 1 robot, which had landed on the moon eight months earlier.

If the Chandrayaan scientists are “really, really lucky,” says Robinson, they might also detect the shadows of the lunar rovers, the two-man buggies that astronauts left at the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 sites. The 10-foot-long rovers would be less than a pixel in size, but their shadows could be as long as four or five pixels, says Robinson.

His own instrument on the LRO will do a thorough job of “revisiting” the Apollo sites, beginning in early 2009. The narrow-angle camera can resolve details about the size of a microwave oven. As the LRO spacecraft orbits from pole to pole and the moon turns slowly beneath it, it will eventually get a look at all six Apollo landing sites. The resulting pictures should clearly show the landers and the rovers, says Robinson. Even some of the larger experiment packages left behind by the moonwalkers might be identifiable from their shadows. The LRO images should also show rover tracks and the dark areas where the astronauts scuffed up the lunar soil. The new information can then be used to refine maps of the moonwalkers’ historic traverses.

And that’s just Apollo. Some of the most fascinating pictures the LRO takes will show obscure spacecraft that nobody’s seen, or even thought much about, since they left Earth more than 40 years ago. Phil Stooke, a planetary geographer at the University of Western Ontario and author of The International Atlas of Lunar Exploration, has a list of targets he can’t wait to see, including two Russian spacecraft—Luna 9, which in 1966 made the first soft landing on the moon, and Luna 17, which in 1970 delivered the first geological rover, Lunokhod 1. Neither spacecraft’s location is precisely known, says Stooke. Nor are the exact locations of many of the craters made when orbiters and spent rocket stages crashed into the moon in the 1960s. Altogether, about 100 tons of junk is strewn across dozens of spots around the moon. Over the next two years, we’ll rediscover much of it.

Of course, the LRO’s mission is not finding old spacecraft. The orbiter is producing high-resolution maps for planning the next wave of lunar exploration. But since astronauts aren’t expected to head moonward until 2020 at the earliest, the initial users of the maps are likely to be surface-exploring robots, and the first of those could arrive as early as next summer, in time for the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11. An intense contest is under way among several groups vying for the $30 million Google Lunar X Prize, which will go to the first privately funded team that lands a rover on the moon, drives it at least 500 meters (about a third of a mile), and returns video and still images to Earth.

Just as the first X Prize spurred aircraft designer Burt Rutan to build a one-man rocketplane that flew to the edge of space and back (see “Confessions of a Spaceship Pilot,” June/July 2005), the Google prize is meant to encourage innovation in robotic exploration of the moon. So far, 13 teams have entered, from as far away as Romania and Malaysia.

The Rutan in this race is Carnegie Mellon University’s Red Whittaker, one of the world’s foremost roboticists. Whittaker-built rovers have explored volcanoes, deserts, and Antarctic ice fields. Last year one of his vehicles won the DARPA Urban Challenge, a road rally for autonomous robot cars, sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Whittaker’s X Prize team, Astrobotic Technology, is loaded with experience, starting with project manager Tony Spear, the man who led the NASA mission that in 1996 landed the Sojourner rover on Mars. The University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, currently operating the Phoenix spacecraft on Mars, is a partner. Astrobotic’s president is David Gump, a space entrepreneur who in 1989 started a venture called LunaCorp, which also planned to drive a rover around the moon and sell the video. Whittaker was to have built the robot. Although LunaCorp folded in 2003, Gump is betting that it was mostly because the company was ahead of its time.

Not that Astrobotic’s proposed “Tranquillity Trek” to the Apollo 11 site will be a cakewalk. For one thing, says Gump, the mission will cost about $100 million—far more than Google is paying in prize money. While he looks for financial backers, the technical team is working feverishly, trying to hold on to the possibility of a launch next year. Astrobotic claims that once it raises the money, it can be on the moon within 18 months.

After landing, Astrobotic’s rover will have just 14 days—a lunar day—to reach the Apollo 11 site and take pictures. Equipping the robot to withstand the frigid, two-week lunar night would have complicated the engineering and driven up the cost. So this will be a short, focused sprint to Tranquillity Base. The rover moves at “about a human walking pace,” says Gump, and will have to reach its destination before nightfall, so success requires a precision landing. The team expects to come down about half a mile from its target, with a precision measured in meters—unprecedented accuracy for a robotic planetary lander.

This is where another Astrobotic partner, Raytheon, comes in. The company built the Navy missile that intercepted and destroyed a military reconnaissance satellite falling from orbit last February. Astrobotic will license the Raytheon “digital scene matching” technology used in cruise missiles—which compares real-time pictures of the looming target with photos stored in an onboard computer—to ensure precise navigation.

Another serious contender to win the Google prize is Quantum3, based in Vienna, Virginia, and led by NASA veterans including Courtney Stadd, the agency’s former chief of staff, and Liam Sarsfield, its former deputy chief engineer. Quantum3 is counting on a new method of landing that Stadd says is different from what other teams are using. Then, instead of rolling on wheels, the lander will “hop” around the surface with small rocket blasts. The price tag, says Stadd, is much lower than $100 million, but is still more than the Google prize money. Like Astrobotic, Quantum3 is heading for the Apollo 11 site. As of May, Stadd still hoped his team could make it there by the 40th anniversary, in July 2009.

All the proposed traffic around Tranquillity Base makes some in the space community worry that the historic Apollo sites will get trampled. Beth O’Leary, a New Mexico State University anthropologist who has led a campaign, so far unsuccessful, to declare the Apollo 11 site a national historic landmark, is concerned that the robots could inadvertently destroy a priceless artifact. Despite the best intentions of the X Prize teams, she says, “it’s untried technology.”

So far, it’s a controversy without much argument. “Our top priority is protecting Apollo 11 from any disturbance,” says Gump. “We’re not rolling over any footprints.” Astrobotic’s rover will stay outside the perimeter of Armstrong and Aldrin’s farthest travels, he says. Pictures of the lander will be taken from a “respectful distance” with a telephoto lens.

Gump hasn’t given much thought to what the pictures will show. But he looks forward to the adventure playing out on live TV, “like opening Al Capone’s vault.”

Might the photos, like the vault, prove disappointing? There’s a chance—a very remote one—that the lander has been destroyed by a meteoroid. We know of at least one Apollo artifact that’s still intact, though, right where Aldrin left it on July 21, 1969. Tom Murphy and his colleagues at the University of California at San Diego still interact with it regularly. Every few nights, they point a laser at a quartz prism on the surface. Then the scientists time the beam that bounces back, a measurement useful for gravitational physics studies. In the two years he’s been pinging the Apollo retro-reflectors, Murphy has become increasingly puzzled. Despite the exquisite sensitivity of his instrument on Earth, the signal that bounces back from the moon is 10 times weaker than it should be. After ruling out other explanations, Murphy has come up with a tentative theory: The reflectors left on the moon have degraded over time. Maybe, he thinks, they have been lightly etched by all those sharp dust grains bouncing around for years on the lunar surface. If so, the once-pristine glass may now be frosted, which would explain the loss in signal strength.

It’s the kind of thing NASA engineers planning the next lunar outpost would love to know. The rest of us just want to find out what happened to the flag. We may not have long to wait.

Original here

For the past few days, rumors have been flying around the Internet that the White House was being briefed by NASA scientists about a “provocative” discovery that could indicate the potential for life on Mars. But today, a source close to the planet says it isn’t so. Details after the jump.

For the past few days, rumors have been flying around the Internet that the White House was being briefed by NASA scientists about a “provocative” discovery that could indicate the potential for life on Mars. But today, a source close to the planet says it isn’t so. Details after the jump.