Eric Hand reports on the short life and hard times of the little Mars lander that sort-of-could.

Eric Hand

By the standards of Tucson, Arizona — let alone the northern plains of Mars — Ithaca, New York, is lush in any season. But winter is coming on. The autumn foliage is already past its prime as Peter Smith strides up the steep hill towards the Cornell University campus. It is 14 October, and Smith, a professor at the University of Arizona, is scheduled to give a talk on the status of NASA's Phoenix lander at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Science. Smith is Phoenix's principal investigator, and the only academic ever to have overall responsibility for running a mission on the surface of Mars. He has decided to walk from his downtown hotel to the conference centre, and the unseasonably sunny weather is exacting its toll. A patch of sweat spreads from the centre of his bright orange golf shirt towards the burning, beady-eyed bird emblazoned on his breast: the Phoenix mission badge.

Smith is not the first speaker in the session on ongoing NASA missions; that is local hero Steve Squyres, the Cornell professor responsible for the science packages on Spirit and Opportunity, the rovers that have been trundling across the planet indefatigably since 2004. Squyres bounds up onto the stage in boots and blue jeans: "I've only got 20 minutes for this, so hang onto your seats." After a whirlwind tour of hills climbed, craters visited and geological features studied, Squyres finishes with the latest ambition for Opportunity: a 12-kilometre trek to a crater 22 kilometres across. It could take up to two years to complete.

“The mission's not quite what I thought it would be at the beginning.”

Peter Smith

Smith looks tired as he mounts the stage. He stands back from the podium and flashes a smile. "You know, there's a big difference between Steve and me," he says. "Steve's always moving. I stay in one place. I'm kinda a couch guy, ya know? So our missions are like that, too." But for all his self-depreciation, Smith talks with real pride about what his team of, at its peak, 300 people has done. It has delivered a comparatively cheap spacecraft to the surface of Mars, and set it down on a plain rich in near-surface ice. The analytical lab on board has found evidence of intriguing salts; Smith shows a picture of strange spots on one of the lander's legs that might, conceivably, be water droplets (see 'Strange brew'). Another instrument has found evidence for carbonates, formed in the presence of water, and a weak signal that, Smith says, might just be due to organic molecules — something never detected before on Mars. So much to relish and pursue — if only there were more time.

But there isn't. Whereas Squyre's rovers have had their mission stretched from its original 90 sols — the term used for a Martian day — to 1,700 and counting, nothing like that is possible for Phoenix. The plain it sits on is far to the north of the rovers, and the winter that is swiftly coming on is harsh enough to freeze the thin atmosphere onto Phoenix's body. The scientists running the various instruments are jockeying for a share of the ever-lower power levels as the days get shorter and the sun sinks lower; the end is in sight. The Cornell talk is on the mission's 138th sol. Smith knows that well before sol 200 the mission will be over, the lander dead on its darkling plain.

Reversal of fortune

The mission has taken its toll on Smith, normally a gregarious, happy-go-lucky man. During the talk, he charms the audience with his humour. But over lunch he is uncharacteristically downbeat, even testy. "It's not quite what I thought it would be at the beginning," he says, picking at his food. "We're right there, next to a soil that has all these wonderful secrets locked into it. We've got the right instruments, we've got the right people involved, everything is perfect. And we can't quite get those bits of scientific knowledge out of our instruments. It's a frustration, I tell you. We're going right down to the wire."

Phoenix was a child of misfortune. After the success of Mars Pathfinder in 1997, the first landing on Mars since those of the Vikings in 1976, NASA's Mars programme managers had taken up then-Administrator Dan Goldin's mantra of "faster, better, cheaper", trying to deliver two small, innovative spacecraft to the planet every two years. But in September 1999, Mars Climate Orbiter burned up in the planet's atmosphere because no-one had noticed a confusion between metric and imperial units in the navigation commands. Three months later Mars Polar Lander (MPL) was lost as it made its way to a site near the planet's South Pole, probably because its thrusters shut off while it was still 40 metres up in the air.

Taking no more chances, in 2000 NASA cancelled a lander planned for 2001 that would have used the same design as MPL. And a proposed orbiter, the Mars 2003 Surveyor, lost its launch opportunity to Squyres' rovers. This put Smith in dire straits. Smith had run the main camera on Mars Pathfinder, and had MPL survived he would have done the same on that mission. He had also been working on providing and running cameras for both the cancelled missions, work now curtailed. "I had no job. I lost 35 employees. I had no mission." Smith went to work for University of Arizona colleague Alfred McEwen, who was managing the Hi-Rise camera for the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, due to fly in 2005.

But faster, better, cheaper was not quite dead. In 2002, NASA opened up a competition for a new 'Mars Scout' line of low-cost missions, modelled after its Discovery missions to the rest of the Solar System. Smith got back into the fray. He was the cameraman on six of the Scout proposals — and the principal investigator on a proposal of his own. "No matter who won," he says, "I would win too."

Bill Boynton oversees development work on Phoenix.H. ENOS

Bill Boynton oversees development work on Phoenix.H. ENOSSmith's proposal, Phoenix, was an ingenious one. It would use hardware from the abandoned 2001 lander to run a mission similar to the ill-fated MPL — but flipped from one pole to the other. Bill Boynton, a burly, balding colleague of Smith's at the University of Arizona, and also a veteran of MPL, was in charge of a γ-ray spectrometer on Mars Odyssey, an orbiter launched in 2001. He was finding evidence of broad haloes of near-surface hydrogen extending out from the planet's polar ice caps. The implication was that there was water ice in the plains, and that it was close enough to the surface to be studied with little more than a trowel. The northern plains seemed to be as icy as MPL's target site in the south, but with the advantages of being flat, mostly boulder-free and at much lower elevation. A spacecraft landing there would have considerably more atmosphere to slow it down before reaching the surface.

The Phoenix proposal suggested a landing on those northern plains with two specific goals: to study the history of water in the Martian arctic, and to assess the biological potential of the boundary between the ice and soil, in search of evidence of an environment that might be habitable. In 2003, to the surprise of many, Phoenix won the competition to become the first Mars Scout, beating a range of less risky missions. As on the Discovery missions, Smith would be in charge of everything. A project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, would supervise the contracts and construction of the mission. But Smith's out-of-the-way university would be the operational home.

So beautiful, so new

Sol 0: Principal investigator Peter Smith celebrates Phoenix's safe touchdown, as depicted on the mural outside the mission's science operations centre.A. POULSON; L. K. HO/AP

Sol 0: Principal investigator Peter Smith celebrates Phoenix's safe touchdown, as depicted on the mural outside the mission's science operations centre.A. POULSON; L. K. HO/APSmith's science operations centre is in a residential neighbourhood a few kilometres from the university campus in Tucson. It is a low-slung, stucco building amid the dun-coloured homes, anonymous but for a bright, almost garish mural showing Phoenix's descent to Mars. On 25 May — sol zero — hundreds of scientists, engineers and their families gathered there to munch on picnic food and watch the tracking information relayed to Earth via Odyssey and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter as Phoenix's interplanetary voyage came to an end.

In what the team was calling the 'seven minutes of terror', Phoenix plunged through the thin air. The blackened heat shield was jettisoned. The parachute opened. Mission controllers called out altitudes. Twelve retro-rocket thrusters began a rapid fire dance of high-pressure hydrazine. After a final twist to orient itself to maximize the amount of sunlight its solar panels would absorb, Phoenix touched down. It was the first landing on Mars since the Vikings to use rockets, not air bags, to cushion the descent, and in the imaginations of the scientists and engineers back on Earth it had done so flawlessly. In Tucson, people cheered and clapped and cried. "The landing was probably the biggest high of the whole mission," says Smith. "We were told over and over and over again to expect it to fail."

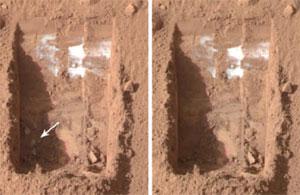

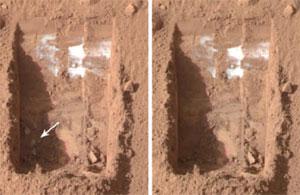

Sol 20: Phoenix spots possible chunks of ice (arrow) in the Dodo-Goldilocks trenches. By sol 24 they are gone (right).NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UNIV. ARIZONA/TEXAS A&M UNIV.

Sol 20: Phoenix spots possible chunks of ice (arrow) in the Dodo-Goldilocks trenches. By sol 24 they are gone (right).NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UNIV. ARIZONA/TEXAS A&M UNIV.The influx of data was, at first, as smooth and splendid as the landing had been. As the scientists adapted their bodies to sols instead of days — an extra 40 minutes every 24 hours leads to something like permanent jet lag — Phoenix's main camera, mounted two metres above the plain, started on a panorama. Early shots revealed cracks in the soil that marked out polygons of different sizes. The cracks hinted at cycles of warming and cooling that had changed over time — in sync, perhaps, with oscillations in the tilt and orbit of Mars. The lander's robot arm reached out and scratched at the ground, and on sol 20 the camera saw some pale nuggets at the bottom of a trench a few centimetres deep. Four sols later they were gone; it was ice that had sublimed from solid to vapour after being exposed to the balmy warmth of the polar summer: −31 °C that day, according to the lander's meteorological station.

The pictures were meant to be just an appetizer; the main course was to be soil samples fed into Phoenix's eight tiny bellies, each of them an oven that could bake its contents to 1,000 °C. Phoenix's nose, a mass spectrometer, would sniff the gases given off, detecting compounds down to concentrations as low as 10 parts per billion. The whole ovens-plus-spectrograph system was the Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyzer (TEGA), and it was crucial to the mission's goal of seeking out organic compounds in the soil. Viking had failed to find such compounds; but TEGA had hotter ovens and a landing site where, some argued, the iciness of the soil would preserve organic compounds well (see Nature 448, 742–744; 2008). Such compounds might not be evidence of life — various apparently lifeless sites in the Solar System have complex carbon chemistry — but they would speak to Phoenix's goal of assessing habitability.

TEGA, based on a similar instrument that had flown on MPL, was run by Boynton. The man who was detecting ice from orbit with one spectrometer would also melt it down on the Martian ground to sniff its isotopes with another. TEGA was at the heart of Phoenix's planned science, Boynton says. Its results were the most eagerly anticipated, and its care and feeding took up a great deal of the team's time. Impressively, the workhorse had been put together for just $13.6 million by a dozen university scientists and technicians. But TEGA was temperamental from the moment it was put to work.

By this distant northern sea

In April 2007, a few days before TEGA was shipped from Tucson to Lockheed Martin in Denver, where it would be bolted onto the spacecraft, a short circuit was found in a filament inside the mass spectrometer. It was not a fatal flaw; there was time to clear up the problem, and the instrument had a second filament as backup. On sol 4, though, the backup filament was found to have a short circuit, leaving TEGA without a safety net and heightening the stress on Boynton's team. Towards the end of June, on sol 25, another short circuit was discovered, this time in one of the oven units, probably caused by the shaking the unit was subjected to as the spacecraft operators tried get some surprisingly sticky soil through a grating. Again, the short wasn't fatal — it affected only one of the ovens — but it added to the nervousness both in Tucson and at NASA headquarters.

On missions led by principal investigators, such as the Discoveries and Scouts, NASA is supposed to defer to the scientist in charge on all matters of scientific operation. But Phoenix was high profile and some of its instruments a little erratic. At headquarters, everyone from Administrator Michael Griffin down was involved in daily reviews of the mission, says Doug McCuistion, Mars exploration programme chief at NASA. At the end of June, word came down that the Phoenix team was to treat its next TEGA sample as its last, and to go after a sample of rock-hard ice before it did anything else. The Tucson team had lost its autonomy.

"We stepped in, I'll be honest," says McCuistion. Boynton — a bit of a bulldog when it came to keeping control over his instrument — acknowledges the logic: "NASA was really afraid … that if we never got the ice it would be embarrassing." But he and Smith still resent the way that the mission was taken over. "That's not the way you do these things," says Smith. "That's why we were pushed at the end."

It took the team days to figure out how to get the scraps of ice, shredded with a rasp, into the arm's scoop. Then, when the scoop was turned over above one of TEGA's ovens, the ice refused to fall out. Even when the team figured out how to sprinkle some out, it was faced with what would become the most nagging of the mission's problems: the doors to the ovens only opened partway. Much of what came out of the scoop didn't make it into the ovens.

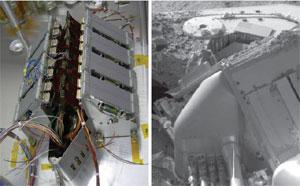

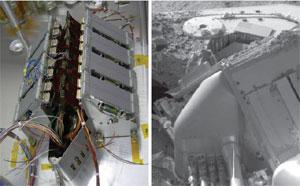

The Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyzer looked fine in the lab (left), but on Mars, soil samples didn't always make it inside.NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UNIV. ARIZONA/MAX PLANCK INST.

The Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyzer looked fine in the lab (left), but on Mars, soil samples didn't always make it inside.NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UNIV. ARIZONA/MAX PLANCK INST.What made the glitch most maddening was that the mistake had been caught before launch. One of the differences between the TEGA on Phoenix and that on MPL was a thin retracting cover to keep the instruments from being contaminated by any stowaway microbes from Earth. Boynton and his team had noticed, on a test version of TEGA, that the brackets at the bottom of this cover were just a hair's width too big, and as a result obstructed the doors. They sent revised designs for the cover to the manufacturer, Honeybee Robotics of New York. New parts were delivered and installed. But Honeybee had made the new parts using the original flawed designs — and nobody in Tucson checked them. "They should've caught it and we should've caught it, but neither of us did," says Boynton, ruefully.

Boynton says that the problems with TEGA weren't lost capabilities, but lost time: "the clock was running against us". After three unsuccessful weeks attempting to get some pure ice into an oven, the NASA directive was relaxed, and the Phoenix team went for its preferred option: scrapings of icy soil. There was enough ice in the soil for TEGA to confirm that it was water, but not enough to measure its isotopic make-up — a measurement that could have provided insights into the history of the planet's water and atmosphere. In August and September, TEGA went on to cook up several more shallow soil samples, and found strong signals for calcium carbonate, which is typically found precipitated out of water. More intriguing to Boynton was a low-temperature signal in all the samples — the same signal that Smith had hinted at in Ithaca. It probably came from a different type of carbonate, but it could have been the trace of an organic molecule.

The breath of the night wind

On sol 153 — a few days before Halloween, and a few weeks after Smith gave his talk at Cornell — Boynton celebrates his 64th birthday and convenes the final TEGA planning session in his office on campus. The mission scientists have long since vacated the science operation centre; only Smith and some support staff remain there. Boynton has a bandage on his left hand where a mishap with a coffee machine has left him with a third-degree burn; TEGA hasn't been much kinder. The previous evening Boynton had heard from mission engineers that Phoenix had entered a 'safe' mode — the "do no harm" response programmed into spacecraft as a way to deal with unexpected circumstances — and that commands to Phoenix to shut down its heaters, an attempt to conserve power, had not gone through. But there is still a chance that the TEGA team will get the power, and time, for one last experiment. With his good hand, Boynton wipes crumbs of celebratory chocolate and pumpkin cake from the table and he and his engineers sit down to go over blocks of programming code to be radioed up to Phoenix. They have done this hundreds of times before in the lifetime of the mission. Sunlight streams in through a large glass window, filled nearly to the edges of the frame by the crags of Mount Lemmon, which looms over Tucson. "This is the last block I'm ever going to have to write," says one of the engineers.

They pour over their packet of code — instructions to some valves to open and some to shut — looking for errors. The goal is to suck an atmospheric sample into TEGA and draw out all the carbon dioxide, leaving proportionally higher concentrations of trace gases. The mass spectrometer would then measure the isotopes of argon and other noble gases, which in turn would offer up information about the history of Mars's atmosphere.

They know their best-laid plans may not come to pass, just as they have not in the past. They are ready for the end, which will bring both relief and grief. "It's really has been a lot more emotional than I expected it to be. We wanted it to do a little bit more," says Heather Enos, the TEGA instrument manager. "But isn't that always human nature?".

“There's some relief when it's over. On the other hand, it seems over too soon.”

Peter Smith

In many ways, the trials and tribulations of TEGA are representative of those of the entire mission. At $428 million, Phoenix was a 'low-cost' mission that took on significant risk. According to Boynton, there is no way that one of NASA's traditional operation centres, such as JPL, could ever have operated it for less than half a billion dollars, or built an instrument like TEGA for $13.6 million. "JPL would just say you can't do it, you gotta do it for this much or not at all. We figured there was a shot we could do it. But we did cut corners." A similar, but much fancier, instrument on JPL's vastly overbudget $2-billion Mars Science Laboratory, the launch of which was last week put off for two years to 2011, has cost about $80 million. It is being assembled by 50 scientists and engineers.

Gentry Lee, JPL's chief engineer for Solar System exploration, says that Phoenix will be remembered for getting "remarkable bang for the buck". The lander performed science on almost every sol of its 157-sol life. It baked samples in five of eight of its ovens, and used three of its four wet chemistry beakers; it never tested the ice, but it tested icy soil. It took more than 25,000 pictures. Its atomic force microscope saw plate-like particles 100 times smaller than those spotted in the best resolution images from the rovers' microscopic imagers. Its main camera saw snow falling from overhead clouds, and frost gathering on the ground.

Boynton says that they didn't reach the optimum point on the science per dollar curve, and he wishes, especially, that they had more money for post-mission analysis, given that the scientists had so little time to work with data during the mission. He is still working on Earth-based controls that might help to decipher that enigmatic low-temperature, probably carbonate signal from TEGA. But he doesn't regret the way things turned out one bit. They stayed within their cost caps. And they delivered. Maybe not to the doorstep, but at least to the front yard. "You can't expect the toast to always fall butter-side up."

Like a land of dreams

The next night, when Phoenix finally takes leave of this world, Peter Smith sleeps through its slipping away. At seven the following morning, he answers the door to his home in NASA-labelled athletic shorts, having just woken up to an e-mail with the subject 'Not so good news'. "You picked a heckuva day to come," he says. The sun, still low, has yet to bake off the desert's night-time chill.

Despite efforts to turn off power-hungry heaters, the lander, with its batteries drained, has gone beyond its safe mode to 'Lazarus mode', an autonomous state in which it tries to operate fixed programs but no longer takes new commands on board. Engineers will monitor weak signals for three more days but never regain control. The science mission has ended.

But the time to grieve has not yet come, because the dog must be walked. Smith puts on his running shoes and grabs the leash. Happy, his exuberant one-year-old mutt — "some sled dog," Smith mutters, still bleary — is already bouncing. Happy charges past the barrel cactus in the front yard and Smith, tugged along, wrestles for the words that describe the end that he knew would come. "There's some relief when it's over. On the other hand, it seems over too soon."

Lee, who has seen generations and missions come and go, says that there is a place for Mars missions of all styles and sizes. Big, expensive flagships for the jobs that cannot fail; smaller, cheaper missions for the ones that can; and, occasionally, medium-sized ones that take dead parts and make them live again. Phoenix has shed light on the results of the Viking experiments, and it is already influencing the way that scientists practice with the scoop on the Mars Science Laboratory. Mars missions are mutually indebted in a way missions to more seldom visited places cannot be — it is part of the luxury of a destination less than a year's rocket ride away. An exploration programme committed to staggered missions, built on what came before, provides some solace in the face of disappointment. But it's hard to deny the pathos of a mission that goes from landing to ending in five months, with many hopes unrealized.

Tucson is getting hotter by the minute. In a desert 374 million kilometres away, Phoenix is chilled to the bone, waiting for the solid CO2 that will soon freeze from the sky to entomb it. Peter Smith, 61, will soon be out of his job as a principal investigator, and he will never run a spacecraft again. Happy noses in the dirt, sniffing for something that's probably organic.

Original here