The test chamber is one of the biggest in Europe

Engineer Neil Wallace peers into a huge vacuum chamber designed to replicate - as far as possible - the conditions of space.

Cryogenic pumps can be heard in the background, whistling away like tiny steam engines.

Using helium gas as a coolant, they can bring down the temperature in the vacuum chamber to an incredibly chilly 20 Kelvin (-253C). The pressure, meanwhile, can drop to a millionth of an atmosphere.

This laboratory in a leafy part of Hampshire is where defence and security firm Qinetiq develops and tests its ion engines - a technology that will take spacecraft to the planets, powered by the Sun.

Ion engines are an "electric propulsion system". They make use of the fact that a current flowing across a magnetic field creates an electric field directed sideways to the current.

This is used to accelerate a beam of ions (charged atoms) of xenon away from the spacecraft, thereby providing thrust.

Neil Wallace, technical lead of the electrical propulsion team at Qinetiq, winds open the door of the testing chamber.

|  The most exciting time for us will be when that space craft comes over the horizon The most exciting time for us will be when that space craft comes over the horizon  |

He points to some large metal blocks at the bottom of the chamber.

"These are the xenon pumps and these are cooled down by the helium compressors to approximately 20 degrees Kelvin," he explains.

"So any gas atoms that strike those panels, they freeze. After you've been running the engines for a number of hours you can see a frost - it looks like snow - which is actually frozen air and xenon."

During testing, the engine fires ions towards the opposite end of the chamber, which has a protective coating of graphite.

"The ions are travelling very fast, at approximately 50km a second," he says.

"When they strike the other end of the chamber, they actually knock atoms off the surfaces they strike; it's analogous to sand-blasting on an atomic level."

Cruise control

The ion engine developed by Qinetiq, the T5, will be flown for the first time on the European Space Agency's Goce spacecraft. The mission will fly just 200-300km above the Earth, mapping the tiny variations in its gravity field.

| GOCE - EUROPE'S GRAVITY EXPLORER 1. The 1,100kg Goce is built from rigid materials and carries fixed solar wings. The gravity data must be clear of spacecraft 'noise' 2. Solar cells produce 1,300W and cover the Sun-facing side of Goce; the near side (as shown) radiates heat to keep it cool 3. The 5m-by-1m frame incorporates fins to stabilise the spacecraft as it flies through the residual air in the thermosphere 4. Goce's accelerometers measure accelerations that are as small as 1 part in 10,000,000,000,000 of the gravity experienced on Earth 5. The UK-built engine ejects xenon ions at velocities exceeding 40,000m/s; Goce's mission will end when the 40kg fuel tank empties 6. S Band antenna: Data downloads to the Kiruna (Sweden) ground station. Processing, archiving is done at Esa's centre in Frascati, Italy 7. GPS antennas: Precise positioning of Goce is required, but GPS data in itself can also provide some gravity field information |

A replica of the T5 engine sits in the test facility at Qinetiq. It is tiny - weighing 3kg, and looks rather like the oil filter of a car.

Yet despite this humble appearance, it took 20 to 30 years to develop, at a cost of tens of millions of pounds.

In space, ion engines will draw electric power from solar panels, generating a thrust equivalent to the weight of a postcard.

This incredibly gentle thrust could, in theory, take a spacecraft beyond our Solar System, if sustained for long enough.

Goce is staying very close to Earth, flying in an ultra-low orbit, where it will encounter wisps of air.

The benefit of an ion engine on this mission is to provide drag compensation, or cruise control.

"This spacecraft is [travelling] at a speed of about eight and a half kilometres per second," says Neil Wallace.

"As it travels around the Earth, it's going through the upper atmosphere and it experiences a buffeting.

"They need to compensate that buffeting very accurately and that's what we're doing, so we're actually providing cruise control for that spacecraft."

Real flight

Various types of ion engine have been used before on only a handful of space missions, including Smart-1, the European mission to the Moon, and Nasa's Deep Space 1, which flew by a comet.

The T5 ion engine being tested |

Future Esa missions such as BepiColombo, bound for the innermost planet, Mercury, will also use the technology.

Qinetiq gets to test its T5 engine for real this summer, when Goce is launched from the Russian space port of Plesetsk. It will go up on the same type of rocket that failed three years ago, destroying Europe's Cryosat ice mission.

Neil Wallace says the nature of the space business makes watching any launch a dramatic event.

"You spend 10 years working on a mission, treating the components and equipment like a newborn baby. You never take it out of the clean room, and then you put in on the top of 100 tonnes of high explosive and set light to it," he says, laughing nervously.

"But no, the most exciting time for us will be when that spacecraft comes over the horizon and the ground station picks it up, and you can see the engines are doing what we've always said they will do."

Original here

It's been known for a while that restricting your diet will increase your lifespan, but now researchers have shown one reason why: Eating less causes your ribosomes (your cells' protein factories) to mutate. And it's looking like mutated ribosomes (pictured here) could be one key to life extension. The good news is that you may not have to starve yourself to mutate your ribosomes anymore. Biologists at the University of Washington have managed to induce the life-extending mutation in ribosomes with a drug that doubles the lifespan of yeast cells.

It's been known for a while that restricting your diet will increase your lifespan, but now researchers have shown one reason why: Eating less causes your ribosomes (your cells' protein factories) to mutate. And it's looking like mutated ribosomes (pictured here) could be one key to life extension. The good news is that you may not have to starve yourself to mutate your ribosomes anymore. Biologists at the University of Washington have managed to induce the life-extending mutation in ribosomes with a drug that doubles the lifespan of yeast cells.

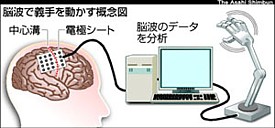

Researchers at Osaka University are stepping up efforts to develop robotic body parts controlled by thought, by placing electrode sheets directly on the surface of the brain. Led by Osaka University Medical School neurosurgery professor Toshiki Yoshimine, the research marks Japan’s first foray into invasive (i.e. requiring open-skull surgery) brain-machine interface research on human test subjects. The aim of the research is to develop real-time mind-controlled robotic limbs for the disabled, according to an announcement made at an April 16 symposium in Aichi prefecture.

Researchers at Osaka University are stepping up efforts to develop robotic body parts controlled by thought, by placing electrode sheets directly on the surface of the brain. Led by Osaka University Medical School neurosurgery professor Toshiki Yoshimine, the research marks Japan’s first foray into invasive (i.e. requiring open-skull surgery) brain-machine interface research on human test subjects. The aim of the research is to develop real-time mind-controlled robotic limbs for the disabled, according to an announcement made at an April 16 symposium in Aichi prefecture.